Android has become a diverse, multi-faceted, and complex ecosystem. In our

research, we came across a Xiaomi Redmi Note 11S and wanted to get root. This is

our journey from unprivileged user-land to the most secure layer of Android

through a chain of three (or four) bugs as

presented at 39c3.

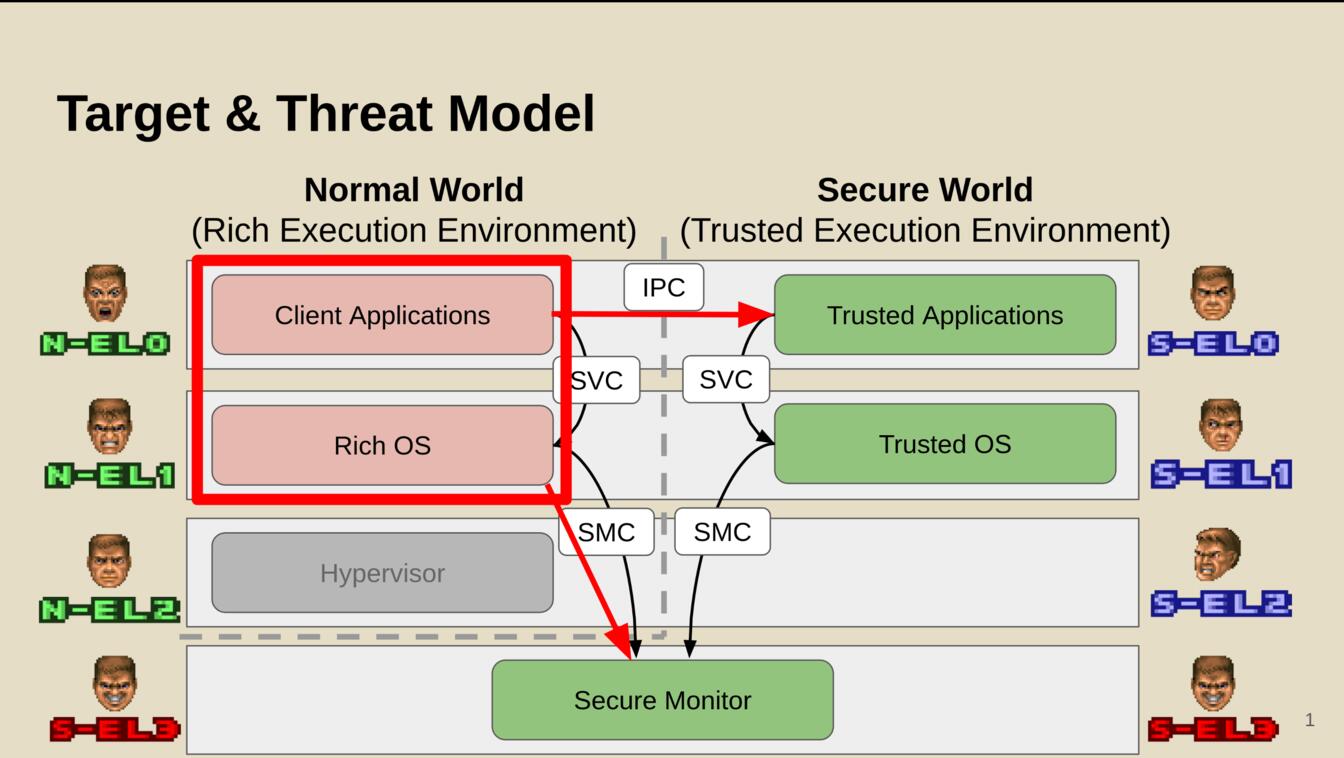

In our chain, we assume that an attacker already has root access on the Android

device. This may be achieved through a malicious app giving them user-space

access and a kernel bug to escalate their privileges from the normal world

exception level 0 (N-EL0) to the normal world kernel (N-EL1). While the attacker

can already control other apps, ARM knows an even more privileged mode called

the "Secure World". Android uses the secure world to protect private data,

cryptographic keys, and sensitive applications. We show how to get full

privileges at the highest exception level in the secure world through a chain of

three (or four) bugs.

Setup: Get root (or die trying)

To get access to debug logs and to control the kernel (as per our threat model),

we first have to get developer access. On the Xiaomi Redmi, this involves

setting up a cloud developer account, registering device using a data SIM, waiting for a

week, and finally unlocking it to get developer access. While this is tedious,

it's a straightforward process. As more and more OEMs try to make this process

as hard as possible, Xiaomi is actually one of the OEMs that makes this

comparatively easy.

So we started with a COTS Redmi Note 11S and, after a week of waiting, we gained

developer access and root in the normal world. We don't have access to

the secure monitor (running at S-EL3) or the secure world (yet). Our applications can

interact with the secure world through the Global Platform API. The Secure World

is hidden and protected from the normal world (and the device owner).

Bug 0: Global confusion

We observe that MediaTek ships the keyinstall trusted application by

default, which is then included on all Xiaomi devices. In an earlier version, we

reported a type confusion vulnerability (CVE-2023-32835

<https://nvd.nist.gov/vuln/detail/cve-2023-32835>). The essence of this bug is

a type confusion when calling query_drmkey_impl, giving the attacker an

arbitrary write primitive in the TA through keytypes_out:

uint32_t query_drmkey_impl(keyblock_t *keyblock, ..., uint32_t *keytypes_out, ...) {

keycount = keyblock->keycount;

curr_keyslice = (keyslice_t *) &keyblock->keyslices[0];

i = 0;

do {

memcpy(&keyslice_copy, curr_keyslice, KEYSLICE_SZ);

keytype = keyslice_copy.keytype;

keytypes_out[i] = keytype;

key_slice_len = keyslice_copy.drm_key_size + KEYSLICE_SZ;

curr_keyslice = (keyslice_t *)(&curr_keyslice + key_slice_len);

i += 1;

} while (keycount != i);

[...]

We published this GlobalConfusion

bug pattern in 2024 and disclosed all discovered vulnerabilities in TAs to the

respective vendors. MediaTek promptly fixed the bug and checks for correct type

usage in the updated version. Also, the Global Platform consortium since

incorporated our suggestions to make the type check explicit.

Bug 1: Rollback attack

On many Android ecosystems, including RedMi, trusted applications are loaded

from the normal world into the secure world where they are executed. As, per the

threat model, the attacker controls the normal world, the loading must be

secured.

Trusted applications are therefore signed and verified before they are

executed. While signatures enable authenticity, they do not enable freshness. As

bugs are fixed in trusted applications, old applications still have a valid

signature. The trusted world therefore must implement some form of version counter

to ensure only the newest versions can be loaded.

Unfortunately, the keyinstall application has no rollback prevention.

Assuming root privileges in the normal world, we leverage a Magisk overlay to

provide the old (vulnerable) keyinstall trusted application and load it into the secure world

where we can exploit the previous bug.

Pivot 1: Code execution in the secure world

By leveraging bug 0 and bug 1 above, we achieve an arbitrary write primitive in

the trusted application. On the RedMi beanpod TEE, trusted applications run in a

32-bit address space without ASLR. Our simple strategy to get code execution is

to search for an RWX page and hijack control flow. We first use our arbitrary write

primitive to scan for writable pages by using our write primitive to iterate

through pages. This gives us a list of pages we have write access to. We now

write a return instruction (bx lr) to the page and overwrite a GOT entry to branch to

our code gadget.

After finding an RWX page, we neatly place our shellcode there and get

convenient code execution as a user-space process in the secure world.

Bug 2: Access to physical memory

While user space access is nice, we obviously want the highest level of

privileges. The Beanpod trusted execution environment runs the Fiasco L4Re

microkernel. In a microkernel environment, the kernel provides a minimal trusted

computing base that only manages essential tasks for process abstractions,

memory management, and inter-process communication (IPC). Processes get assigned

capabilities to communicate with other trusted processes that manage hardware or

other privileged tasks.

As a first step, we therefore enumerated the capabilities that our compromised

keyinstall trusted application had. Interestingly, we have

the memory_client_* and sst_client capabilities. Reversing the

uTMemory process, we discovered that it has the sigma0

capability, allowing it to map any physical memory. Through this chain from our

compromised TA through uTMemory to sigma0 we can now map arbitrary physical

memory, thereby gaining read/write access to all memory, including memory of the

secure monitor and other trusted applications.

This bug essentially means game over for security and indicates a privilege

inversion. Through capabilities of our user space process, we are allowed to map

arbitrary physical memory into the address space of our process. This makes

further escalation a walk in the park.

First lesson of compartmentalization: make sure your policy is tight and secure.

Don't hand out capabilities like candy and make sure each application runs with

least privileges.

Bug 3: Stack smashing as a detour

Now assuming that the Fiasco capabilities were not misconfigured and that

apps cannot map arbitrary physical memory, we would have to find a lateral path

through other apps slowly escalating our privileges. Looking at our

capabilities, we have access to sst_client which allows us to interact with

sst-server. The sst-server app has access to memory_client, so this is a

juicy one-step target.

Squinting at the sst-server and browsing through uses of memcpy we immediately

find a stack-based buffer overflow that gives us simple code execution. This

would have served as a fallback to gain memory_client capabilities if the

capabilities were not broken in the first place.

Second lesson of compartmentalization: applications with access to privileged

capabilities must be secured as they are an important attack surface. Attackers

may target them to get access to their capabilities or use them as confused

deputies.

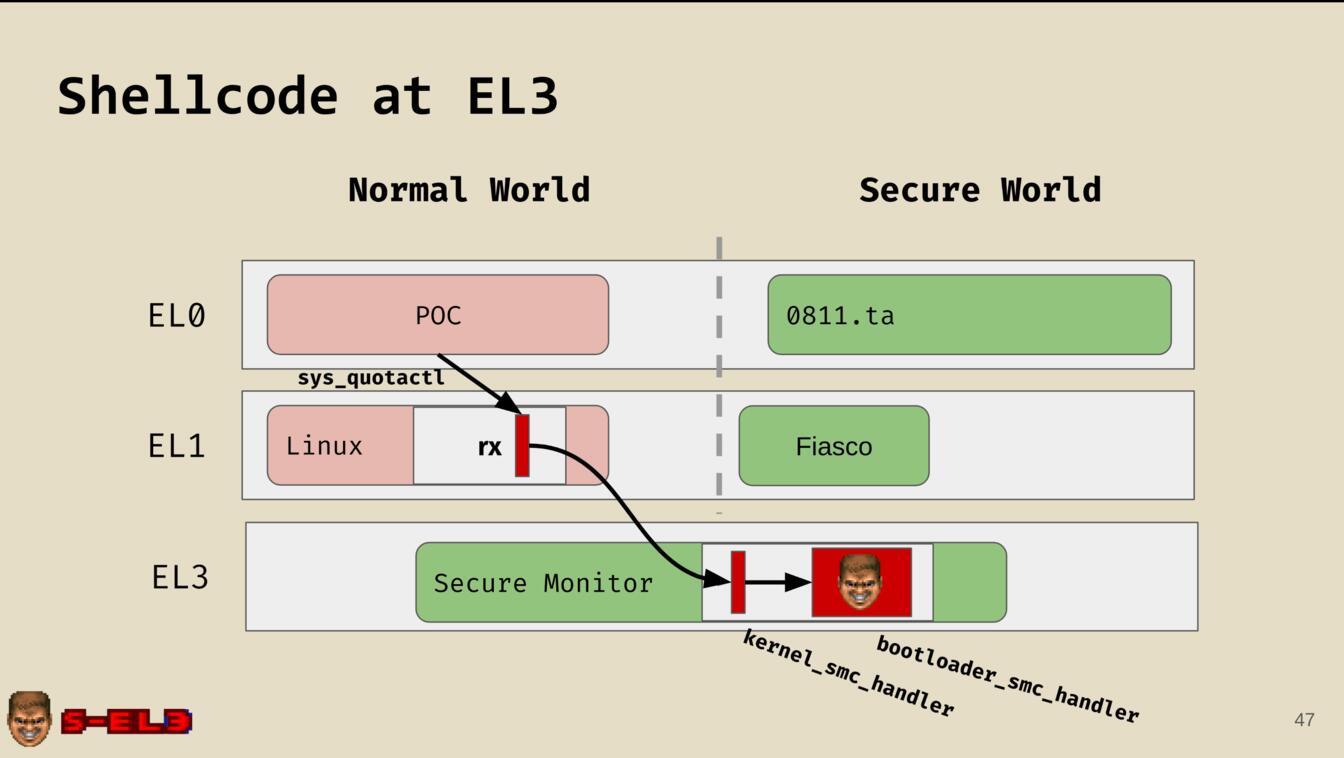

Pivot 2: From trusted application to controlling the secure world

Our goal is now to invoke code in the secure monitor from the normal world as

executing code there is much more convenient. Following our first pivot, we use

the new capabilities to map the physical memory of the secure monitor into the

address space of the trusted application we control.

We patch one SMC handler in the secure monitor to execute our code

(namely the bootloader_smc_handler that is likely unused after boot). To

make it callable from user space, we also overwrite the code of a system call

handler in the Linux kernel in the normal world (namely the sys_quotactl

that is likely unused) to trigger the secure monitor smc call through a

svc call.

With this chain, we now have a reliable way to trigger our shellcode in EL3.

FTW: pin bypass and DRM keys

We now demonstrate the capabilities of our new privileges by demonstrating an

arbitrary pin bypass and leaking DRM keys.

PIN Bypass. Searching the physical address space for the pin verification function running

in a trusted application, we locate the page with the corresponding code and

patch the function to return true. This allows the device to accept any pins and

tells the user land that login succeeded.

Leaking DRM keys. Using a similar primitive to scan physical memory, we

interact with a DRM provider and then locate and leak the device key.

Interestingly, this would allow us to emulate and rehost the DRM solution to

dump 4K streams (of movies we paid for).

Parting thoughts

Apart from demonstrating an amazing hack and the first public

exploit chain for the Beanpod TEE, this research demonstrates the weaknesses of highly

compartmentalized systems. The TEE ecosystem is incredibly complex and a chain

of mistakes allows an attacker to compromise the full ecosystem.

When deploying compartmentalization, we must carefully assign capabilities based

on least privileges and secure exposed services by vetting them and deploying

mitigations. Also, the (trusted) app ecosystem should be carefully controlled

with the minimal amount of apps allowed possible.

On our target device, we managed to escalate from N-EL0 to S-EL0 through a

rollback attack that allowed us to exploit a known type confusion vulnerability.

This initial foothold enabled us to enumerate capabilities and list dependency

chains. We then escalated from S-EL0 to S-EL3 by mapping arbitrary physical

memory due to a capability misconfiguration (but could alternatively have done

so by exploiting a stack based buffer overflow in a slightly longer chain).

Check out all details in the beanpod_fiasco repository, watch the recording of the talk,

or check out the slides.

Join us if you're interested in low level Android

research, compartmentalization, or just general mischief.

Philipp deserves the main credit for writing the exploits and reversing the

underlying apps, Marcel was the driver behind the global confusion bug pattern

and the rollback attacks.